Patterns in Street-Names: Literature and the Arts

By Paul Tempan

In previous blogs I have looked at some of the themes found in Belfast street-names, such as those named after big houses and street-names transferred from London. (For an introduction to Belfast street-names and an overview of patterns, see Tempan 2023.) This time I explore names inspired by literature and the arts in general, with a little detour into the role played by street-names in music and literature. Some of these occur as clusters in specific neighbourhoods, while others are isolated examples scattered across the city.

A good place to start is with Shakespeare, although it will soon become apparent that he does not top the rankings in Belfast. The Bard is represented by Titania Street and Oberon Street which allude to the King and Queen of the Faeries in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Glendower Street very probably belongs to this group, as Owen Glendower [Owain Glyndŵr, Prince of Wales]  features in Henry IV, Part 1. All of these are off Cregagh Road. Elaine Street in Stranmillis recalls a figure from Arthurian legend and title character of a poem in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (Marshall, 12). There was also a Tennyson Street [1899] (BPU 1899) off Springfield Road, but Tennyson is also a surname that occurs locally, so it may not necessarily be named from the poet. Moonstone Street [1901] (BPU 1901) is a little-known street between Lisburn Road and the railway which may allude to Wilkie Collins’ detective novel The Moonstone (1868). However, this can only be a tentative suggestion as the neighbourhood also includes Capstone Street and Larkstone Street, which, as far as I know, are not part of a literary theme. They only seem to be connected by sharing -stone as the second element.

features in Henry IV, Part 1. All of these are off Cregagh Road. Elaine Street in Stranmillis recalls a figure from Arthurian legend and title character of a poem in Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (Marshall, 12). There was also a Tennyson Street [1899] (BPU 1899) off Springfield Road, but Tennyson is also a surname that occurs locally, so it may not necessarily be named from the poet. Moonstone Street [1901] (BPU 1901) is a little-known street between Lisburn Road and the railway which may allude to Wilkie Collins’ detective novel The Moonstone (1868). However, this can only be a tentative suggestion as the neighbourhood also includes Capstone Street and Larkstone Street, which, as far as I know, are not part of a literary theme. They only seem to be connected by sharing -stone as the second element.

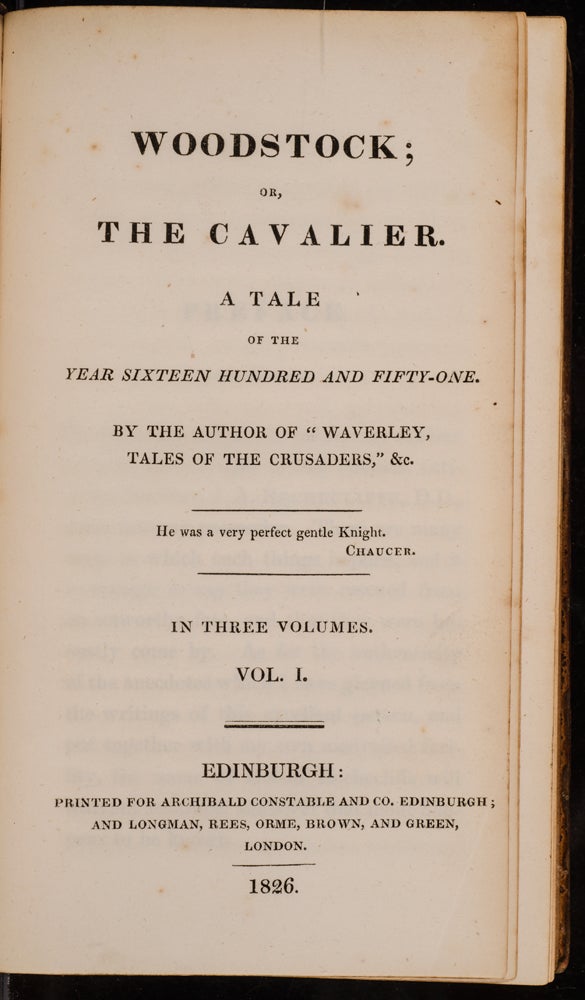

Sir Walter Scott was clearly a particular favourite of builders and developers, and is represented by Ardenvohr Street, built in 1897 (the Knight of Ardenvohr is a character in A Legend of Montrose), Clanchattan Street [1890] (Clan Chattan and Clan Quhele engage in an epic combat in The Fair Maid of Perth), Glenvarlock Street (Nigel Olifaunt is Lord Glenvarloch in The Fortunes of Nigel, note the discrepancy in spelling), Wayland Street (from Wayland Smith, a character from Kenilworth) and Woodstock Road [1863] (IHTA xvii, 40) (from Woodstock, or The Cavalier). John J. Marshall quotes Scott’s The Lay of the Last Minstrel in relation to Melrose Street [1896] (IHTA xvii, 29; Marshall, 20), but nearby are Lorne Street and Edinburgh Street, so it may simply be part of a Scottish place-name theme, and without contemporary documentation it is impossible to be absolutely sure of the motivation behind the name. Marshall also mentions Abbot Street [Abbott Street, 1878] (from The Abbot, Scott’s historical novel set during the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots), Peveril Street [1876] (from Peveril of the Peak) and Ivanhoe Street [1877] (these three streets being near the gas-works on Ormeau Road), as well as Rokeby Street (off Castlereagh Road) from a Scott poem ‘Rokeby’, but these have all since been demolished for re-development (Marshall, 1, 17, 22, 24–5). The novel Ivanhoe is still remembered in  the Ivanhoe Inn on Saintfield Road at Carryduff, and there is also an Ivanhoe Avenue in the vicinity. I would also suggest that Matilda Avenue / Drive / Gardens in the Sandy Row estate may well be part of the Walter Scott theme. These streets have replaced the earlier Matilda Street [1868] (IHTA xvii, 28). I have no hard evidence of this link, but there is an Oswald Park is nearby, which replaced the earlier Oswald Street [1892] (IHTA xvii, 32). Matilda Rokeby and Oswald Wycliffe are characters in Scott’s poem ‘Rokeby’ (1813). The earliest of these names inspired by Scott seems to be Woodstock (from the novel published in 1826), which occurs first in Woodstock-Place, Mountpottinger, mentioned in 1846 as the residence of David Maginnis, who ran a boarding and day school for young gentlemen (Northern Whig, 13/01/1846, p. 3). This is likely to be the origin of Woodstock Road, named 17 years later. Whether Maginnis was the first owner and was, perhaps, the Scott afficionado responsible for starting this trend in Belfast, is uncertain. It seems likely Revd. D. Magennis, who ran a school at Donegall Place W. in 1850, is the same person (Henderson’s Directory, 1850).

the Ivanhoe Inn on Saintfield Road at Carryduff, and there is also an Ivanhoe Avenue in the vicinity. I would also suggest that Matilda Avenue / Drive / Gardens in the Sandy Row estate may well be part of the Walter Scott theme. These streets have replaced the earlier Matilda Street [1868] (IHTA xvii, 28). I have no hard evidence of this link, but there is an Oswald Park is nearby, which replaced the earlier Oswald Street [1892] (IHTA xvii, 32). Matilda Rokeby and Oswald Wycliffe are characters in Scott’s poem ‘Rokeby’ (1813). The earliest of these names inspired by Scott seems to be Woodstock (from the novel published in 1826), which occurs first in Woodstock-Place, Mountpottinger, mentioned in 1846 as the residence of David Maginnis, who ran a boarding and day school for young gentlemen (Northern Whig, 13/01/1846, p. 3). This is likely to be the origin of Woodstock Road, named 17 years later. Whether Maginnis was the first owner and was, perhaps, the Scott afficionado responsible for starting this trend in Belfast, is uncertain. It seems likely Revd. D. Magennis, who ran a school at Donegall Place W. in 1850, is the same person (Henderson’s Directory, 1850).

Sir Walter Scott was held in great esteem by the Victorians, to the extent that he was compared by some to Homer, praise which may seem a little overblown nowadays. The 19th century mania for his works has been highlighted by Professor Richard Coates in relation to the naming of locomotives. In this area, as with our Belfast streets, more names were coined from the works of Scott than from those of Shakespeare or Dickens (Coates 2023, 441).

Other writers also feature, such as François-Marie Arouet, the French author known as Voltaire (1694–1778), commemorated in Voltaire Gardens in Whitewell (Marshall, 30), and Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81), whose novel Lothair of 1870 is remembered in Lothair Avenue [1880] (IHTA xvii, 26; Marshall, 18), near Limestone Road. Marshall also mentions Coningsby Street [1889] in Oldpark (IHTA xvii, 14; Marshall, 7), which alluded to another popular Disraeli novel of 1844, but which no longer exists. There is also Disraeli Street [1877] (BPU 1877), situated in Upper Shankill between Woodvale Road and Crumlin Road. Disraeli Court, Disraeli Close and Disraeli Walk are more recent additions in the same neighbourhood. Byron Street [1865] (IHTA xvii, 12) off Oldpark Road commemorated the romantic poet Lord George Byron (1788–1824), but this too is gone. One can see from the above how themes in street-names have sometimes been eroded by re-development. However, of Copperfield Street [1889] (IHTA xvii, 15) Marshall remarks that it is ‘curiously enough the one street that can be credited to Charles Dickens. No surname of Twist, Nickleby, Gamp, Micawber or Pecksniff adorns a nameplate on our street corners’ (Marshall, 8). And of Thackeray, whom he describes as ‘Dickens’ great rival, he says that Esmond Street is his only link to Belfast’ (Marshall, 12). Both Copperfield Street and Esmond Street seem to have resulted from single acts of commemoration which were never developed into a theme. Both are now gone.

Very few Irish / Northern Irish writers are remembered in our street-names, but there are a few exceptions, such as Jonathan Swift (1667–1745). Swift Street in Ballymacarret, named in 1874 (IHTA xvii, 37), has been superceded by Swift Place in the same neighbourhood. Lilliput Street [1870] (IHTA xvii, 26) in Tiger’s Bay was discussed in an earlier blog. It is named from Lilliput, a house built in 1760 by David Manson, a teacher, and the house in turn was named after the island of the tiny people in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726). Gulliver’s Avenue in the Harbour Estate runs north from Dargan Road.

Clive Staples Lewis (C. S. Lewis, 1898–1963), author, theologian and scholar, best known for The Chronicles of Narnia series of books (1950–56). Lewis grew up in Strandtown, East Belfast. He spent much of his adult life in England but frequently returned to Belfast. In 1998, his centenary year, he was commemorated with a sculpture by Ross Wilson entitled The Searcher, installed in front of Holywood Arches Library. It shows the character Digory Kirke opening a wardrobe in a scene from The Magician’s Nephew, the book which tells the origin story of Narnia. The sculptor’s representation of Kirke is modelled on Lewis as a young man. In 2016 C. S. Lewis Square was opened as a public square showcasing other sculptures of characters from The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, the first book of The Chronicles of Narnia. New streets close to this square have been named Lewis Drive, Lewis Avenue, Lewis Park, Lewis Gardens and Lewis Mews. Not far away is Victoria Park, which is now connected to Airport Road by Sam Thompson Bridge, opened in 2013. Playwright Sam Thompson (1916–65) is best known for Over The Bridge (1957), a stage play which tackled the thorny topic of sectarianism, and the television play Cemented With Love (1965), which deals with political corruption.

There is no Belfast street named after any of Ireland’s four Nobel literature laureates, Yeats, Shaw, Beckett or Heaney. However, Glengormley has Sally Gardens and Dunmurry has Sally Garden Lane, which both recall Down By The Salley Gardens, one of the best loved poems of William Butler Yeats (1865–1939).

Street-names in literature and music

Having considered the topic of street-names inspired by writers, it is worth noting that there are also plenty of instances of the reverse phenomenon, namely writers drawing inspiration from the city’s streets and districts. There are several examples in the  music of Van Morrison, such as the tracks Cyprus Avenue (1968), Connswater (an instrumental piece, 1983), Orangefield (1989) and On Hyndford Street (1991). The last of these is a hushed spoken word piece from the album Hymns To The Silence, the title referring to the street where Morrison was born. It is packed with childhood memories imbued with spiritual significance, like “going out to Holywood on the bus” and “stopping at Fusco’s for ice-cream”, and it references a number of places in the East Belfast of Morrison’s youth, such as Abetta Parade, Cyprus Avenue, Cherry Valley, Orangefield, St. Donard’s Church (“Sunday six-bells”), Beechie River, The Castlereagh Hills and Craigie Glens [Cregagh Glen].

music of Van Morrison, such as the tracks Cyprus Avenue (1968), Connswater (an instrumental piece, 1983), Orangefield (1989) and On Hyndford Street (1991). The last of these is a hushed spoken word piece from the album Hymns To The Silence, the title referring to the street where Morrison was born. It is packed with childhood memories imbued with spiritual significance, like “going out to Holywood on the bus” and “stopping at Fusco’s for ice-cream”, and it references a number of places in the East Belfast of Morrison’s youth, such as Abetta Parade, Cyprus Avenue, Cherry Valley, Orangefield, St. Donard’s Church (“Sunday six-bells”), Beechie River, The Castlereagh Hills and Craigie Glens [Cregagh Glen].

Books named after Belfast streets include Eureka Street (1996), a novel by Robert McLiam Wilson which follows the lives and romances of two friends in divided Belfast during the Troubles; and Snugville Street (2015), Angeline King’s novel about a working-class Belfast family coming to terms with the realities of life after the conflict (Snugville Street is named after a house on Shankill Road which is recorded in 1814 (IHTA xii, 36). In 1843 it was the residence of Edward Walkington, wholesale druggist [= pharmacist], oil and colour merchant, commissioner for taking affidavits and special bail. His business premises was at 11, Rosemary Street.) Snugville Street still exists, a side-street off  Shankill Road, but Eureka Street in the Sandy Row area is gone, replaced by Eureka Drive. (The origin of the name Eureka Street is unclear to me. It was coined in 1870 (IHTA xvii, 18). It does not seem to fit with any of the other themes noticeable in the Sandy Row area. As “eureka!” is an exclamation of discovery, perhaps it is significant that Felt Street National School was nearby if the motivation was related to learning. Permission was granted to build this school in 1875 and Eureka Street is also mentioned in its address (IHTA xvii, 77)).

Shankill Road, but Eureka Street in the Sandy Row area is gone, replaced by Eureka Drive. (The origin of the name Eureka Street is unclear to me. It was coined in 1870 (IHTA xvii, 18). It does not seem to fit with any of the other themes noticeable in the Sandy Row area. As “eureka!” is an exclamation of discovery, perhaps it is significant that Felt Street National School was nearby if the motivation was related to learning. Permission was granted to build this school in 1875 and Eureka Street is also mentioned in its address (IHTA xvii, 77)).

However, there can be few works which mine this rich vein of material as thoroughly as Ciaran Carson’s The Star Factory (1997), a largely autobiographical novel in which the streets and landmarks of Belfast assume a role almost as prominent as the human characters. It is described as follows in the paperback blurb: ‘In The Star Factory, he [Carson] makes himself the cartographer of his home city's spaces, symbolic and literal, the scribe of its byways and avenues, from Abbey Road to Zetland Street.’ It can be seen from these examples that the city’s extraordinarily rich stock of street-names, referring to a huge diversity of people, places and things, effectively constitutes a kind of dictionary, atlas and Who’s Who, all rolled into one — an encyclopaedia ideally made to fire the Belfast literary imagination.

Other names connected with the arts

Other spheres of the arts are also represented: Landseer Street in Stranmillis, is named after Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–73), an artist known particularly for his paintings of animals, such as the magnificent stag depicted in Monarch of the Glen (Marshall, 17). Vandyck Crescent, Vandyck Drive and Vandyck Gardens in Whitewell, are named from Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), a .jpg) Flemish artist who became court painter to Charles I of England. (These streets may also be part of a local cluster in Whitewell, along with Voltaire Gardens and Veryan Gardens, a group connected by nothing more than sharing the initial letter V. Veryan is a village in Cornwall). Gainsborough Drive in North Belfast may be named after the artist Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88), if not after the town in Lincolnshire. One of Thomas Gainsborough’s works provides a link with Belfast, an outdoor portrait of Arthur [Chichester], 1st Marquess of Donegall, which is in the Ulster Museum’s collection (catalogue number BELUM.U35, painted c. 1780).

Flemish artist who became court painter to Charles I of England. (These streets may also be part of a local cluster in Whitewell, along with Voltaire Gardens and Veryan Gardens, a group connected by nothing more than sharing the initial letter V. Veryan is a village in Cornwall). Gainsborough Drive in North Belfast may be named after the artist Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88), if not after the town in Lincolnshire. One of Thomas Gainsborough’s works provides a link with Belfast, an outdoor portrait of Arthur [Chichester], 1st Marquess of Donegall, which is in the Ulster Museum’s collection (catalogue number BELUM.U35, painted c. 1780).

Ruskin Street [1902] (BPU 1902), off Springfield Road, was a street that existed for only a couple of decades in the early 20th century, named after John Ruskin (1819–1900), influential writer, art critic and polymath. Its presence in this area tends to confirm that nearby Tennyson Street, equally short-lived, was indeed named after the poet. Conor Rise [1996] (BPU 1996) and Conor Close off Stewartstown Road may be named after the Belfast-born painter William Conor (1881-1968), famous for painting street-scenes.

Bentham Drive in the Sandy Row area, is named from Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), English philosopher and social reformer, best known as the founder of modern utilitarianism; in the same vicinity, very aptly, are Utility Street and Utility Walk, named from Bentham’s principle of utility.

The architect Sir Charles Lanyon (1813–89) is remembered in Lanyon Place, now also the name of Belfast’s main railway station, formerly Belfast Central Station. Lanyon was born in Eastbourne, England, but spent much of his working life in Ireland, particularly Belfast. He was responsible for designing many of the city’s landmark buildings including Belfast Castle, the Custom House, Crumlin Road Gaol and Courthouse, the core part of Queen’s University Belfast (known as the Lanyon Building), Sinclair Seaman’s Presbyterian Church, the Palm House in the Botanic Gardens, the Linenhall Library and Union Theological College. He was elected Mayor of Belfast in 1862 and was MP for the city 1865–68.

Photo: Belfast Castle, designed by Sir Charles Lanyon. Photo: Paul Tempan.

A commercial enterprise intimately connected with the city’s artistic life in the 19th century was Marcus Ward & Co., stationers, printers and publishers. The business was established in 1843, became one of the largest printing firms in Europe, specialising in chromo-lithographic printing, and continued until 1901.

The founder is commemorated in Marcus Ward Street, a side-street of Dublin Road which, until May 2021, ran alongside a multiplex cinema. This cinema stood on the site of the company’s Royal Ulster Works, built in 1873 (Patton 1993, 139). The space is now occupied by Trademarket. Marcus Ward Street leads to Hardcastle Street, named after William Hardcastle Ward, a partner in the same firm (Patton 1993, 180).

Epilogue

It can be seen from this whistle-stop cultural tour of the city that there is a wide range of Belfast street-names with links to literature and the arts, even if some examples are uncertain. The context can often help to clarify the origin, such as the date of creation and the names of neighbouring streets. We have seen how the context (Ruskin Street being nearby) helped to confirm the inclusion of Tennyson Street in this theme. There are other candidates which were ultimately excluded due to context. Egmont Gardens in the Sandy Row area reminds one of the play Egmont (1788) by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832). However, the presence of Schomberg Drive in the same neighbourhood, referring to the Williamite general, suggests that the allusion is probably to the real-life figure who was the drama’s protagonist. Lamoral, Count of Egmont (1522–1568), was a hero in the Low Countries for opposing the Inquisition in Flanders, for which he was executed by the Spanish.

Some examples occur in clusters, which provides more context, but many more occur in isolation. (In Britain there are many towns which have residential areas where all the streets are named after writers or poets. This has become something of a cliché in urban development. For example, Welling in South-East London has a group of streets named Chaucer Road, Milton Road, Dryden Road, Keats Road, Wordsworth Road, Tennyson Close, Shelley Close, Browning Close, Blake Close and Burns Close. David Nobbs, author of The Death of Reginald Perrin (1975, later adapted for television as The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin), played on this suburban trope by having his protagonist Reggie live on a "Poets' Estate" at 12, Coleridge Close. Belfast has no comparable clusters with such an extensively developed literary theme. However, there are examples of large clusters in other themes, such as geographical names.) In order to get the full picture, it is necessary to consider streets of the past as well as those that exist today. The Irish Historic Towns Atlas and the various Belfast street directories (many available online at https://www.lennonwylie.co.uk) are vital sources in this respect. Many of the writers and artists commemorated in the 19th century were English or Scottish, and all were male. In the 20th century more streets were named commemorating creative people with a direct connection to Belfast. The author commemorated with the most names is Sir Walter Scott, literally ‘streets ahead’ of all others with an impressive dozen. Disraeli and C. S. Lewis have proved popular too. Almost all of the names coined in the 19th and early 20th century had “Street” as the final element. The street-network at this time was typically arranged in rows or a grid pattern. Many of these have been replaced in the late 20th century by smaller thoroughfares in a branching pattern, using a wide variety of other final elements — a trend which has been highlighted by James Hennessey in a blog on this site. It is to be hoped that more local artists and authors, and particularly more women will be recognised in the future.

Some examples occur in clusters, which provides more context, but many more occur in isolation. (In Britain there are many towns which have residential areas where all the streets are named after writers or poets. This has become something of a cliché in urban development. For example, Welling in South-East London has a group of streets named Chaucer Road, Milton Road, Dryden Road, Keats Road, Wordsworth Road, Tennyson Close, Shelley Close, Browning Close, Blake Close and Burns Close. David Nobbs, author of The Death of Reginald Perrin (1975, later adapted for television as The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin), played on this suburban trope by having his protagonist Reggie live on a "Poets' Estate" at 12, Coleridge Close. Belfast has no comparable clusters with such an extensively developed literary theme. However, there are examples of large clusters in other themes, such as geographical names.) In order to get the full picture, it is necessary to consider streets of the past as well as those that exist today. The Irish Historic Towns Atlas and the various Belfast street directories (many available online at https://www.lennonwylie.co.uk) are vital sources in this respect. Many of the writers and artists commemorated in the 19th century were English or Scottish, and all were male. In the 20th century more streets were named commemorating creative people with a direct connection to Belfast. The author commemorated with the most names is Sir Walter Scott, literally ‘streets ahead’ of all others with an impressive dozen. Disraeli and C. S. Lewis have proved popular too. Almost all of the names coined in the 19th and early 20th century had “Street” as the final element. The street-network at this time was typically arranged in rows or a grid pattern. Many of these have been replaced in the late 20th century by smaller thoroughfares in a branching pattern, using a wide variety of other final elements — a trend which has been highlighted by James Hennessey in a blog on this site. It is to be hoped that more local artists and authors, and particularly more women will be recognised in the future.

References

BPU = Belfast and Province of Ulster Directory (published annually, 1852–1947, continued as Belfast and Northern Ireland Directory, 1948–96). Belfast.

IHTA xii = Gillespie, Raymond and Stephen A. Royle. 2003. Belfast : Part 1, to 1840 (Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 12, eds Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie). Dublin.

IHTA xvii = Royle, Stephen A. 2007. Belfast : Part 2, 1840 to 1900 (Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 17, eds Anngret Simms, H.B. Clarke, Raymond Gillespie). Dublin.

Carson, Ciaran. 1997. The Star Factory. London.

Coates, Richard. 2023. ‘The Naming of Railway Locomotives in Britain as a Cultural Indicator, 1846–1954’, in Bijak, U., Swoboda, P., & Walkowiak, J. B. (Eds.). (2023). Proceedings of the 27th International Congress of Onomastic Sciences: Onomastics in Interaction With Other Branches of Science. Volume 3: General and Applied Onomastics. Literary Onomastics. Chrematonomastics. Reports. Kraków: Jagellonian University Press. https://doi.org/10.4467/K7478.47/22.23.19014

Henderson, John. 1850. Henderson’s Belfast Directory, and Northern Repository. Belfast.

King, Angeline. 2005. Snugville Street: The Sun Reaps What the Rain Has Sown. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Marshall, John J. and others. Undated. ‘Origin of Some of Belfast’s Street-names’ (typewritten transcript compiled from articles published in articles in The Belfast Telegraph, Dec 1940 - Mar 1941).

Patton, Marcus. 1993. Central Belfast – A Historical Gazetteer. Belfast.

Tempan, Paul. 2023. ‘Patterns in Belfast Street-Names’, Familia: Ulster Geneological Review 2023.

Wilson, Robert McLiam. 1996. Eureka Street. London.